“Groundhog Day”, Buddy said to me prior to this week’s public consultation on draft bylaws 767 and 768. “Remember?”

On Monday, Nov. 18, 2019, mayor Jamie Nicholls chaired a public consultation on draft bylaw 526.8 proposing to establish a 30-metre buffer zone around watercourses and wetlands.

The proposed bylaw — within council’s authority, according to an opinion from one of Quebec’s foremost environmental lawyers — would ban all tree-cutting as well as the owner’s use of machinery within any part of the setback on their own property, including lawn cutting. Any new projects — pools, sheds, decks, gazebos, even replacement of a failing sewage treatment system — would be prohibited.

In the leadup to the consult, the urban planning department was asked to create a map overlay showing the 30-metre line imposed on a municipal cadastral map. The overlay confirmed the proposed bylaw would directly impact hundreds of properties throughout the municipality.

The mayor opened the presentation by telling the room that councillors were deadlocked 3-3, so he had already decided to vote yes to break the deadlock. In other words, don’t waste your breath, folks.

“We’re not doing this to make people angry or to remove peoples’ rights,” Nicholls told the standing-room-only crowd at the Community Centre. “We’re doing this to protect the network of wetlands and watercourses which make up Hudson’s natural spaces.”

Nicholls strove to convince residents this was the price taxpayers needed to pay for protecting Hudson’s natural heritage, thus opening the outrage floodgates and a pushback campaign by the bylaw’s supporters. By that December, the mayor had taken a leave of absence and caucus had agreed to let 526.8 expire without adoption. (It remains on the books, even though it has no effect, a so-called zombie bylaw.)

___________________________________________________

There may be those who have never seen the classic 1993 film Groundhog Day. In it, Bill Murray is a burnt-out weatherman and Allie McGraw the bubbly TV reporter trapped in a time loop centred on an annual celebration of the rodent’s storied ability to predict the weather. Groundhog Day has become a synonym for being trapped in an unpleasant situation without hope of a positive outcome.

On the eve of Groundhog Day, 2024, I’m listening to the recording of that 2019 public consultation. Many of the voices are those of people who spoke out at Thursday’s public consultation. The comments and the tone of the 2019 gathering were remarkably similar to those of 2024.

The difference was that this time, the mayor sat this one out. Apart from her opening and closing comments, Chloe Hutchison and councillors left it to former DG and special projects consultant Martin Houde, urban planning department deputy director Melissa Francis and Paré+ urban planning consultant Vincent Langevin to answer questions. Running the meeting was professional facilitator Marie-Hélene Gauthier.

The mayor’s absence at the front of the room meant that questions concerning the intent of the bylaws went unanswered because they were political. Instead of taxing growth and improvement, why not finance park infrastructure upgrades and new acquisitions with Hudson’s $8 million accumulated surplus or the $1 million plus the town collects from the welcome tax? Or how about a townwide special tax, seeing as how parks and greenspace are for everyone’s benefit?

That’s political, we heard. Save it for the next council meeting (at 7 p.m. next Monday, Feb. 5).

From the outset, it became clear that those answering questions were not familiar with the contents of the draft bylaws or how they propose to modify Hudson’s current zoning, tariffs and land use bylaws. For the vast majority of residents, Sections 10 and 11 of draft bylaw 767 were hopelessly confusing and poorly explained. What renovations cross the 33% threshold by volume? Why is the commercial threshold — 25% of floor area — different than residential? Where does a building’s footprint enter into it? Why should council be the arbiter in determining whether the 20% tax grab in the urban core is in land, cash or both? What constitutes an intensification of existing activities? A change in usage? The difference between an extension and an addition?

The deeper they got into the weeds, the more people realized that the explanations and Cole’s notes they had been given at the two open houses were either misleading or just plain wrong.

Some of the answers came as a shock. The town has no clue what revenues they hope to raise through green fund “contributions,” which suggests to me they don’t know who and what will be taxed. Property owners would have no way of knowing they have triggered the parkland contribution threshold until they find out their building permit will cost them $40,000. The findings of an upcoming parks and recreation study could force a change in the tax structure.

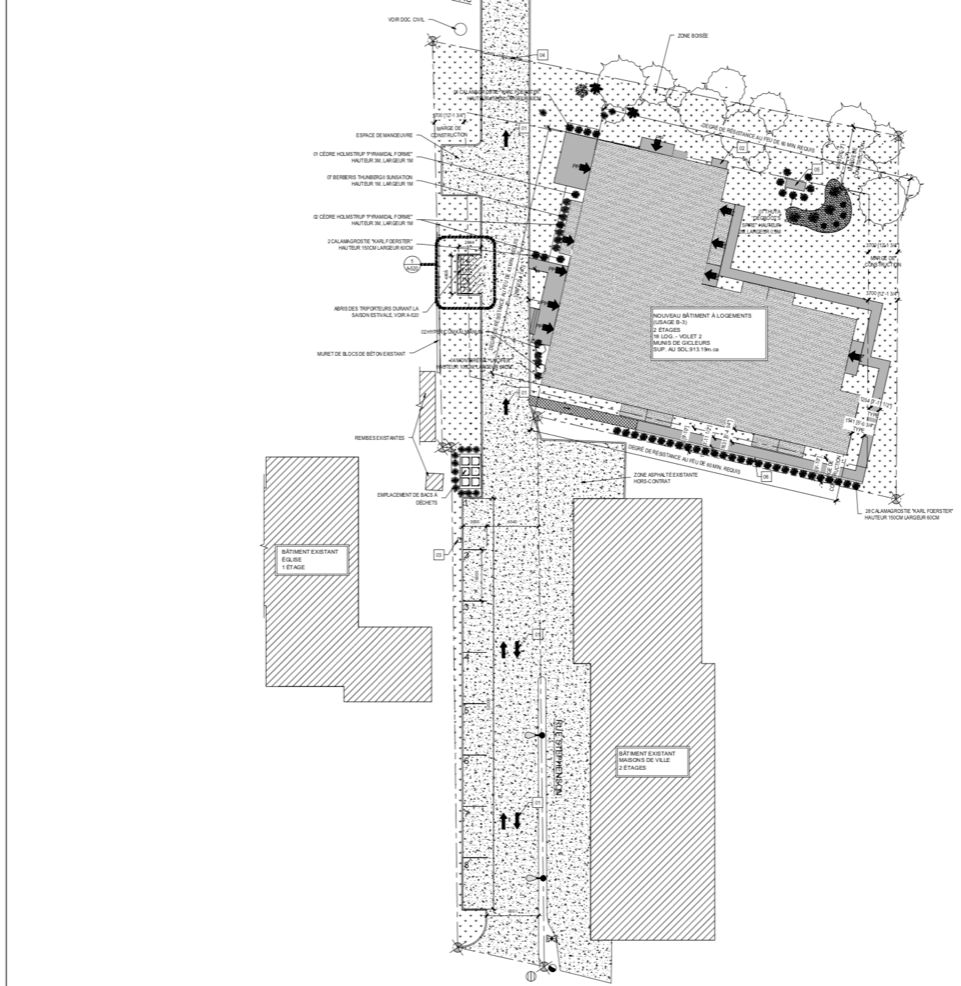

Other sections of both bylaws were no clearer. The owners of a lot in Hudson Valleys were told their lot was unbuildable because it contained a wetland — regardless of the facts that suggest the wetland was created by the buildup of adjacent properties since the original subdivision. Many wondered whether a protected wetland had a minimum area to require a 15-metre buffer. (what, my frog pond?) A resident whose property abuts on one of the four zones slated for comprehensive development programs in draft bylaw 768 asked whether the developer would be required to ensure a minimum treed buffer on the property line (not in the bylaw). Would the town consider paying for the biologist’s report? Why not subsidize the cutting and replacement of ash trees on private land?

Because of the lack of clarity, emotions ran high. Ken Crombie’s questions — shouldn’t all citizens pay for greenspace instead of a small percentage and what can we do to force a referendum instead of letting six councillors decide — brought the first of many rounds of applause as resident after resident vented their frustrations. For many, it was purely personal. “With this bylaw, who will buy a fixer-upper,” one resident asked.

I suspect that this council will be more cautious than our council was in the 2019 showdown. Wiser heads will prevail and the draft bylaws will be sent back for revision. But as several residents opined on Facebook, it makes it difficult to trust a council when something this full of holes is run up the flagpole. Again.