Posted Sept. 18/25:

Now that we’ve read the text of the proposed $9.6M loan bylaw to buy out the owners of Sandy Beach, I’ll repeat the questions I asked at the Sept. 11 special meeting where the notice of motion and tabling of draft were approved unanimously. (Final adoption of the loan bylaw is scheduled for another special meeting this evening.)

Can council guarantee taxpayers will be able to afford this purchase?

Even those passionately in favour of the Sandy Beach buyout have voiced their concerns over the lack of financial details. The text of Bylaw 782-2025 doesn’t address those concerns. Most of it is a lengthy preamble, citing studies, reports and legal actions taken in the 25-year history of the proposed residential development.

Financial details are as follows:

— The Town and owners of the land have reached agreement on the sale of seven lots comprising the proposed development for $8,750,000, excluding taxes and costs. The town does not have the necessary funds to acquire the lots.

— The draft bylaw authorizes council to spend the sum of $9,648,136, including incidental expenses and net taxes, $2M of which will come from the town’s unallocated surplus. An additional $2M grant from the Montreal Metropolitan Community (CMM) remains a possibility. (“We want to keep that door open,” mayor Chloe Hutchison told residents at the Sept. 11 meeting.)

— The remaining $7,648,136 will come from a loan, which like all municipal borrowing requires the approval of taxpayers and the provincial municipal affairs ministry as well as a five-year rollover structure based on prevailing interest rates.

— Borrowing and repayment costs will be charged to the owner of every taxable immovable in Hudson for every unit they own. The bylaw defines a suite thus: serving or intended to serve as a residence for one or more person and where one can prepare or consume meals, sleep and includes a sanitary facility. It may be occupied by either an owner-occupant or rented.

The only exclusion are bi-generational accessory dwellings occupied by or destined to be occupied exclusively for persons having a family, marital or common-law relationship to the second degree with the occupants of the main housing unit.

Commercially, a unit is defined is defined as a space accommodating or intending to accommodate commercial, industrial or craft activities such as the sale of goods or services, either owned by an owner-occupant or rented.

When asked how the per-unit assessment would affect the Manoir Cavagnal and its 90-something units, the mayor said the administration was working on it. A similar response dealt with questions about the cost of securing the beachfront and adjacent forests once it’s open to the general public.

Residents attending the Aug. 27 information meeting were told the term of the loan will be spread over 40 years to minimize the fiscal impact on taxpayers. Although the figure of $121 per unit was given at the Aug. 27 session, the draft loan bylaw doesn’t provide a number. Instead, it entertains the possibility of that $2M grant from the CMM (reducing the annual cost per unit by $35) with the proviso that any “contribution, donation and subsidy” will be used to reduce the loan or defray debt servicing costs.

Simply put, the draft bylaw holds out the hope that federal, provincial or regional governments and NGOs such as Save Sandy Beach will ride to the town’s financial rescue if the tax burden becomes more than Hudson taxpayers can stand.

What the bylaw doesn’t include is the real cost of borrowing $7,648,136 based on a 40-year amortization schedule with five-year resets. Based on an average interest rate of 3.25% for the entire 40-year term, the total cost to taxpayers would be $13.71M, with $6.06M of that in debt interest.

How will it affect the Town of Hudson’s long-term debt? For that, residents can turn to fiscal consultant RCGT’s Cadre financier 2025-2030, an analysis of Hudson’s fiscal roadmap for the next five years.

The RCGT portrait begins with revenues ($14.1M in 2025), more that 80% of it generated by property taxes. Revenues are projected to grow by an average of 4.8% annually, reaching $17.8M by 2030. Most of that growth is generated by real estate transfer taxes, which the town tends to underbudget as a guarantee that Hudson’s annual budgets generate surpluses instead of deficits.

RCGT predicts an average annual budget increase of 4.4% to $21.9M in 2030.

Meanwhile, Hudson’s net debt will reverse a decade-long reduction trend, rising from $22.4M in 2025 to $41M in 2030, a 13.8% increase representing 16% of the 2030 budget — an annual jump of 9.4%. Debt service charges will grow by 10.6% and the debt/revenue ratio ranging between 120% and 155% as the town incurs new debt faster than it can write off old debt.

To soften the annual hit, RCGT advised the town to extend the Sandy Beach loan to 40 years from 30 and to delay construction of a new town hall by two years (2028 instead of 2026) and delaying major reconstruction of a portion of Lower Alstonvale now that preliminary studies show it wasn’t as far gone as first feared.

RCGT predicts Hudson’s debt servicing charges will remain stable through 2027, increasing to $3.6M in 2030 as the town incurs the costs of a new municipal garage and the repaving of Main between Beach and Quarry Point.

Even so, the cost of servicing Hudson’s long-term debt will increase by a third, from $2.2M in 2025 to $3.3M in 2030 — representing 16% of the town’s total 2030 budget.

Asked at the Aug. 27 public information meeting what constraints Quebec might place on Hudson’s long-term debt, RCGT’s Nicolas Plante told the room it was up to taxpayers, not the government.

Here’s my translation of RCGT’s conclusion:

“With a 40-year amortization period, the additional debt related to the Sandy Beach acquisition does not have a significant impact on the debt service ratio in 2030. However, the level of the debt balance increases, and the net debt-to-revenue ratio reaches 166% in 2030.

With this in mind, the City should adopt certain guidelines to control its debt level, such as prioritizing projects (by limiting the maximum borrowing amount per year), using future surpluses to prepay or avoid debt, or implementing a cash payment program for capital assets. These measures will enable the City to maintain an adequate level of debt in line with the challenges of renewing its assets.”

Does any of this matter to Hudson residents? We won’t know until the evening of Wednesday, Sept. 24, the one-day register for those opposed to the bylaw. A referendum would require at least 491 signatures on the register.

Is there a viable opposition? Not from potential mayoral candidates I’ve spoken to. Residents venturing an opinion say they’re of two minds — glad to see an end to a 25-year squabble over plans to develop the 60-acre parcel, concerned by the impact of the loan bylaw on the town’s finances and the lack of clarity on how the town proposes to manage the acquistion.

A big concern is whether the Sandy Beach purchase will tie the hands of future councils. With a 30% increase in Hudson’s long-term debt by 2030 and a 33% hike in debt servicing costs, it’s easy to see how the town might find itself strapped for cash for emergency expenditures, such as replacing a major artery washed away by torrential rains.

One of the presentations at the Aug. 27 info session was how tax revenues generated by Empero’s proposed Pine Beach development would offset Hudson’s growing debt/tax revenue ratio and help pay for future capital works projects. It was dismissed without discussion. The current council has not shown itself interested in densifying the urban perimeter despite threats by the federal and provincial governments to withold funding.

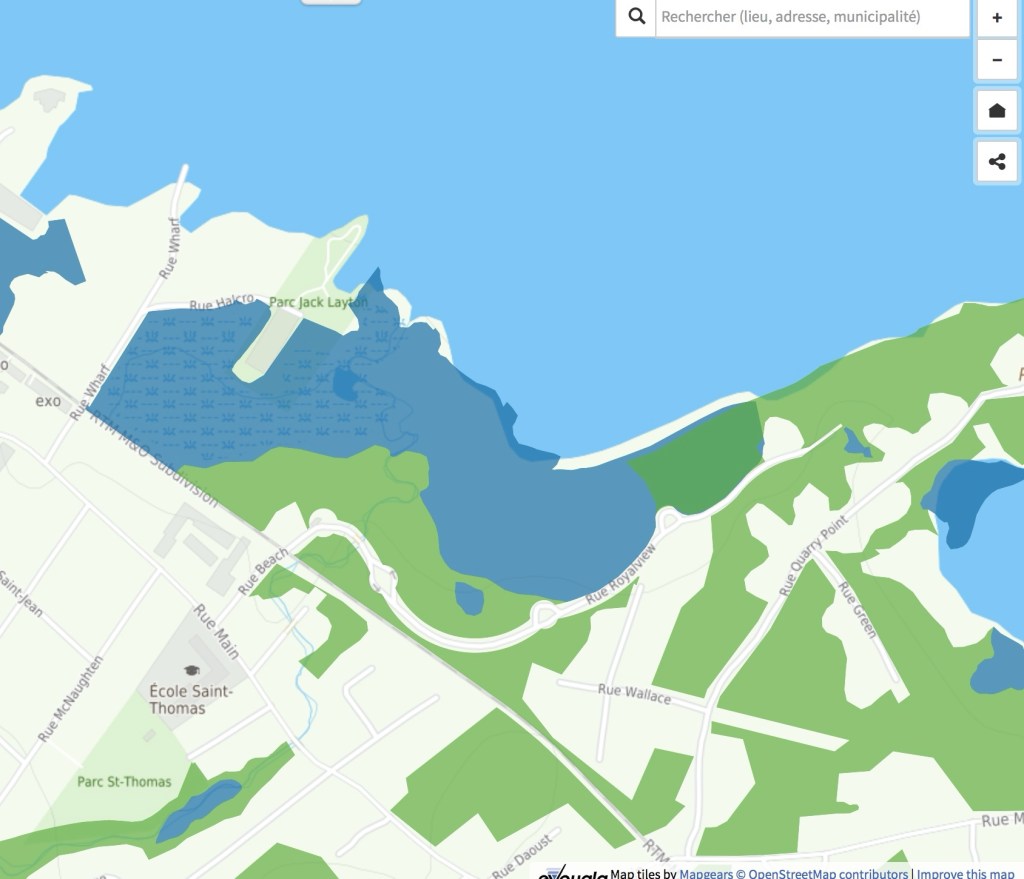

Instead of looking at ways to grow Hudson’s tax base, the current council has spent the past four years looking for legal ways to block Empero’s June 2020 proposal to build 214 residential units on the 24-hectare parcel of land between Jack Layton Park and Quarry Point.

Originally approved as a zoning change by 72% of those who voted in October 2001 referendum, the project has evolved over the years as the result of changes to provincial and regional environmental protection laws and regulations.

Notwithstanding this council’s use of development freezes and bylaw revisions, the town’s legal advice was that the province and the courts will recognize the owners’ right to develop — and to block public access to the town’s beachfront servitude. Mayor Hutchison was left with difficult choices — get Quebec’s approval for new lakefront access or shut down the beach and trail network for the time it took to cut a deal with owners Nicanco Inc. and their partners.

The momentum to buy out the developer began with the August 18 special meeting, where council voted unanimously to authorize town clerk Melissa Legault to sign an offer to purchase seven lots from their current owners for $8.75 million plus taxes. Unlike regular council meetings, the special was not streamed online.

This was where Hutchison told residents a loan bylaw was the fairest way to spread the cost, with $2 million from the town’s accumulated surplus and another $2 million available from the Montreal Metropolitan Community, conditional on equal access to all Greater Montreal residents. Instead of being collected as a membership or assessed by mil rate, a fixed cost per address would present as a line item on tax bills.

This was where we learned the bylaw would be subject to approval by referendum, depending on whether at least 491 eligible residents signed a Sept. 24 registry. There would be an August 27 public information session, where the mayor promised a “respectful, fact-based” process.

The buildup to the Aug. 27 info session included a card in the mail, urging residents to reserve seats if they planned to attend in person where they would learn how the purchase will be financed, its impact on property taxes, conservation and community benefits and the steps in the approval process.

Those who managed to book seats were handed Save Sandy Beach pamphlets at the door to the Community Centre, where it became clear most of the 250 in attendance were there to celebrate their long-awaited victory rather than to ask probing questions about the financials and explore alternatives. A video loop featured drone footage of the beach, the Viviry Creek estuary, wetlands and forests — most of it land already ceded to or controlled by the town. The evening’s introductory slide was entitled Conservation and Access to River’s Edge, setting up the current administration’s contention that those 60 acres can somehow be protected while open to all.

But it became obvious from the outset that even if they are not mutually exclusive, there must be limits. This emerged during citizen exchanges with Nicolas Milot, the CMM’s director of ecological transition, who later explained that if the town were to accept the $2M MCC grant, all four million of its residents would enjoy the same access as Hudson residents — including the beach.

The mayor set up the financial discussion with a more precise cost to taxpayers —$9.6 million, taxes in — and the results of an October 2024 assessment of the land’s market value by real estate assessors LB (you’ll find this and other supporting docs on town website).

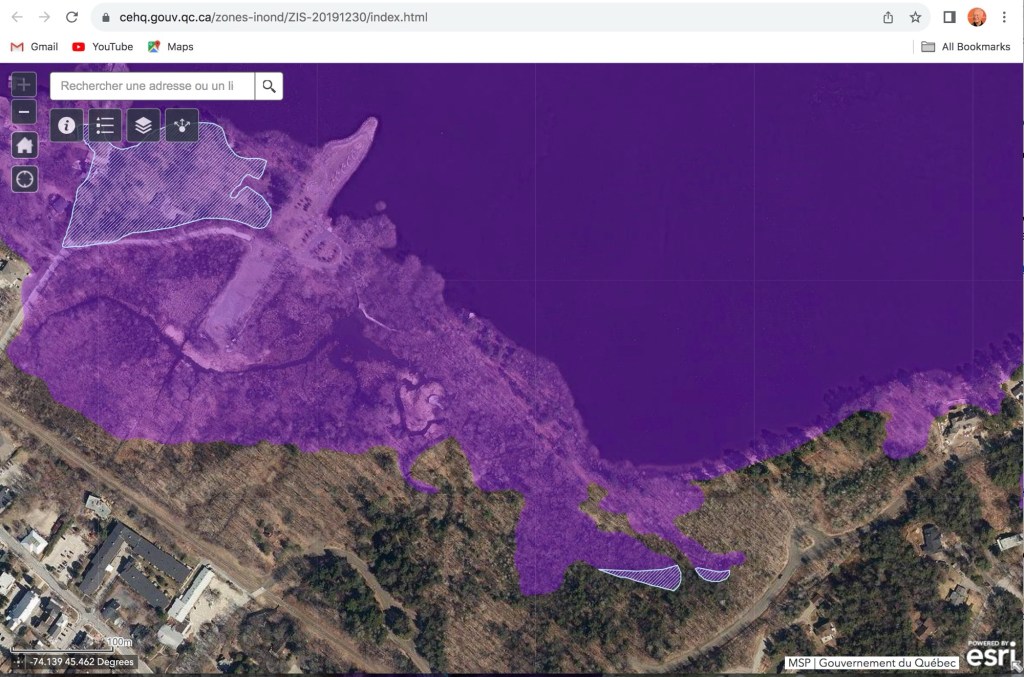

LB’s assessment set a fair market value by setting a realistic price per unit, based on the developer’s 2020 plan for 214 units — reduced by subsequent floodplain maps — and other real estate projects such as St. Lazare’s Place du Parc and high-end residential development on Mont Rigaud. It also considers the cost of constraints — interim control measures instituted by Hudson and the MCC, acreage listed on the province’s contaminated-soil register, contested bans on wetland backfilling and treecutting. LB’s final tally of projected profits: $11.5M for the 214-unit 2020 plan, $10M with all those constraints.

Earlier this year, the town made the owners a lowball offer of $5.5M. It was refused, but the partners countered with the $8.75M response. Why were they ready to sell for so far below market value?

Among the supporting documents is a draft transaction discharge signed this past August 15 by all parties. Once the sale becomes final sometime next year, the discharge ends all legal constraints and seemingly endless litigation by both sides. If the bylaw drive fails at any point in the process, if this council is voted out of office and the deal is killed by the next council, everything reverts to the standoff which has existed for the past 25 years. LB uses the term “best and most profitable usage” to describe any path out of this quagmire. If ever there was such a thing as a legal document with emotion, this is it. They want the endless war to end.