Less than a week in, 2025 is setting itself up to be a pivotal year for the planet. Be it the Liberal leadership meltdown in Ottawa, the MAGA/Musk reality show south of us, Europe teetering on war’s brink, a hair-trigger Middle East or southeast Asia set to explode, far too many hours of our days are spent consuming mostly bad news, driven by a combination of curiosity and dread.

What we don’t hear or read about is the rapidly evolving collection of crises much closer to home, a conflation of feuding bureaucracies and complacent elected bodies and their failure to react to an array of old problems and new challenges — beginning with mobility and public transportation.

According to Quebec’s Institut de la statistique’s 2025 forecast, our county — the regional municipality of Vaudreuil-Soulanges —will have close to 200,000 residents by 2036, but without a coherent plan for a regional public transportation system. Worse, there is no indication the four layers of government we subsidize feel any responsibility to come up with a plan.

Major factors:

— the Bridge. As the transport ministry (MTQ) announced last fall, the replacement Ile aux Tourtes bridge will open in stages, with five temporary lanes moving traffic by the end of 2026, followed a year later with the opening of the six permanent lanes. Until then, residents will continue to face unpredictable traffic jams as a direct result of the MTQ’s improvised fixes, detours and emergency closures to keep the the 60-year-old structure safe for more than 80,000 daily users.

— REM inaccessibility. With a soft opening date in the third quarter of 2025 but no parking for off-island users, Vaudreuil-Soulanges residents won’t be able to access the Anse a l’Orme Réseau express métropolitain (REM) terminal the way they can now find park-and-ride facilities for existing exo train and express bus service at the Vaudreuil station. Of even greater concern to those who depend on Vaudreuil-Hudson train service, exo’s cash-strapped parent Authorité régionale de transport métropolitain(ARTM) has indicated there won’t be money to maintain exo service on any line where a REM option exists.

— broken political promises. In March 2019, then junior transport minister Chantal Rouleau told a closed MTQ briefing of elected officials and concerned citizens the Ile aux Tourtes bridge replacement would be strong enough to carry a light rail transit (LRT) system to the Vaudreuil-Dorion side. (V-S REM: Stupid not to extend, www.thousandlashes.ca; March 11/19) Six months later, the MTQ denied any knowledge of plans to include an LRT right of way (ROW) on the new bridge. Instead, plans show a future ROW running parallel to the new span — in the air.

Did the CAQ or their Liberal predecessors ever intend to bring the REM to Vaudreuil? During the leadup to the October 2022 Quebec election, former Liberal finance minister Carlos Leitao — who oversaw negotiations with Quebec’s Caisse de dépot to enable the creation of the REM — told us plans to bring the REM across the water had already been refocused on running the line across Ile Perrot, then crossing the St. Lawrence to Les Cèdres.

— unjustifiable cost increases. Given the daily chaos on the Ile aux Tourtes, the public had hoped to convince the MTQ to force through transport truck traffic to use Highway 30 and remove tolls for off-island residents. Apart from a few emergency-closure exceptions, neither happened. Effective Feb. 1, tolls on the 30 will rise to $4.60 for most passenger vehicles and $3.45 per axle for anything larger or higher. The rationale? Under the deal with the A30 consortium, the MTQ gets a bigger slice of the take when traffic volume and debt service costs increase (electric vehicles will continue to enjoy free passage).

Effective Jan. 1, there’s also a $100 public-transit surtax on off-island vehicle registrations. Under pressure from the cash-strapped ARTM, the Legault CAQ allowed the SAAQ to levy a $100-per-vehicle increase on annual registrations for residents of the 83-municipality Montreal Metropolitan Community. As I’ll explain below, this has a direct bearing on the future of the new Vaudreuil-Soulanges regional hospital.

Collateral damage

We’re already seeing knock-on effects. Most of us know people who are reluctantly planning the move back to Montreal Island (or have already made the move) because they can no longer cope with epic traffic tieups and have no faith in a better quality of life once the new bridge opens. Other less obvious effects:

— On Dec. 11 we learned the 404-bed Vaudreuil-Soulanges regional hospital won’t open by the end of 2026 as promised. In the best-case scenario cited by the Société québécoise des infrastructures (SQI) the $2.6M project would open in the summer of 2027, six months after the regional health and social services agency (CISSSMO) takes delivery. In the worst case, it would not be operational before the fall of 2028. The aim had been to open the ambulatory care pavilion while work on the main tower continues, but according to CISSSMO this isn’t practical and would only delay completion.

Neither Ile aux Tourtes bridge congestion nor the lack of regional public transit were blamed for the delay, but there are indications they were among the factors as the regional health and social services authority struggles to recruit some 4,000 employees in a region without convenient public transit.

Tasked last summer by the CISSS de la Montérégie-Ouest to propose a reorganization of existing public transit resources to serve the new hospital, an exo team presented a proposal centred on increased shuttle service between the Anse a l’Orme REM station and intermodal hubs at the Vaudreuil and Dorion exo stations where riders would transfer to and from existing CIT bus routes. However, the proposal included this caution: Given the fiscal context and the outlook for 2025, exo has developed a baseline scenario which respects the current budget in trying to meet the reorganization’s original orientations. The scenario remains to be confirmed [depending on the budgetary constraints].

Given the ARTM’s $563M 2024-25 shortfall, will there be new money for a convenient regional public transit network? Quebec’s contribution — $200M to compensate all Quebec municipalities — clearly isn’t enough, so the question becomes what can be cobbled together with the money available.

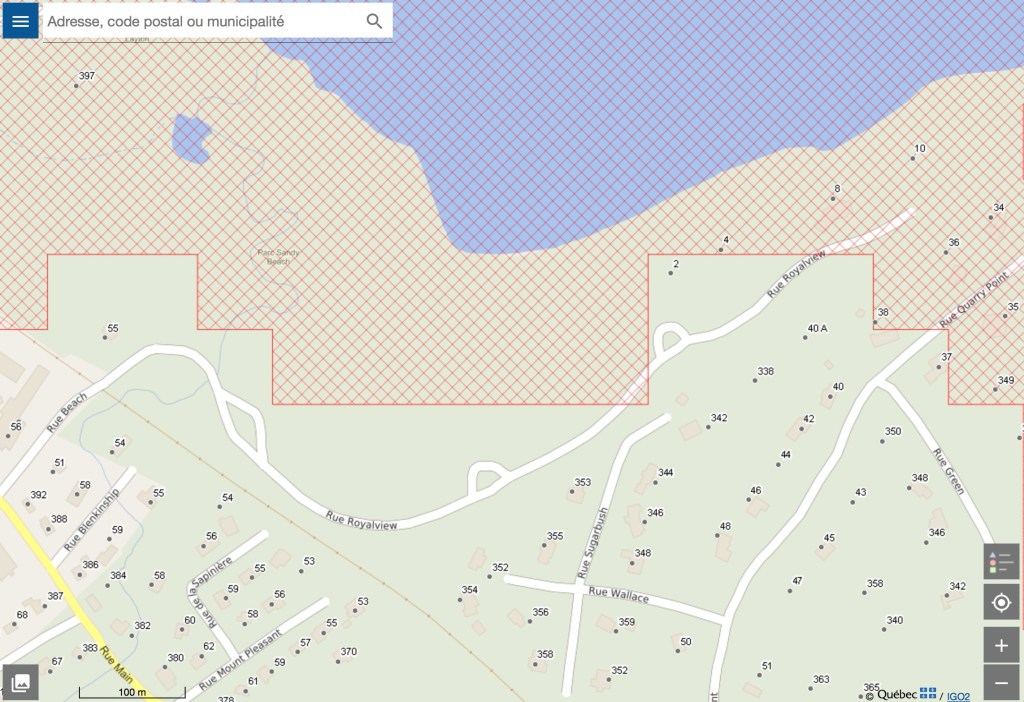

Surprises

With any major project, surprises are the worst enemy. Montreal’s REM was delayed for months by the discovery of century-old live explosives in the Mount Royal tunnel. In the case of the $2,6B Vaudreuil-Soulanges regional hospital, it was the discovery that there isn’t enough pressure in the existing potable water network to ensure pressure to reach the hospital’s 12th storey. Plans had predicted the need for six new wells to supply the complex, but it will require a new pumping station to ensure adequate pressure. How will that affect St. Lazare’s water supply, drawn from the same aquifer? We won’t know until the hospital opens for business.

What should concern us isn’t that our region faces these challenges, but that they’re not being dealt with by those we pay and elect to deal with them. In 2007, the MTQ assured us the existing Ile aux Tourtes span would be good for 70 more years; 10 years later, it was under emergency repair which will continue until its replacement opens. The REM, originally promised to our region, won’t have parking for off-island users; there may not be adequate funding to maintain existing train service. And yet we face exponential increases in fares, tolls, fees and taxes, all without our approval or consent. Like far too much in Canada, this isn’t working.