With barely six months left in this Hudson council’s mandate (last council meeting Oct. 1, with provincewide municipal elections Sunday, Nov. 2), the focus shifts from what it hopes to accomplish to what’s possible with the resources available.

More than three years in, council solidarity is showing serious stress cracks. Dissident councillors Doug Smith (District 1) and Benoit Blais (District 2) said last fall they won’t seek re-election, Blais because he calls it a waste of time, and Smith — no longer welcome at caucus meetings — because he’s rumoured to want the mayor’s job.

Mayor Chloe Hutchison has said she will need a second term to finish what she set out to do. Councillors Reid Thompson (District 4) and Mark Gray (District 5) both said they’re planning to run again. Peter Mate (District 3) told me he hasn’t decided. District 6 councillor Daren Legault, the only holdover from the previous administration, is mulling a third term.

Here’s a partial list of wins, misses and chronic problems:

Staff shortages

A big factor in a town’s success in getting things done is administrative capacity —bureaucratese for being able to hire and motivate competent staff. Hudson’s personnel situation is precarious and depends on stopgap workarounds. The town lacks a full-time director-general since Phil Toone left in May, 2022. Toone’s successor, on medical leave of absence for the past year, got bought out for an undisclosed amount approved at the March meeting, where council also okayed a resolution hiring a headhunter to find yet another candidate. In the meantime, interim DG Martin Houde and assistant DG Susan McKercher will continue to run the town.

Hudson town hall’s infamous revolving door continues to claim treasurers — by my count, seven since the Villandré scandal a decade ago. The last permanent treasurer was shown the door last year. A replacement barely had the time to fill out paperwork before he was canned in favour of a CPA originally hired on a consulting contract to mentor him. The March council meeting renewed that contract, billed between $7,000 and $15,000 a month since the fall.

Contracting out continues at the chronically short-staffed urban planning department, where the turnover has been fierce among inspectors. Gestim, UP’s outsourced permits and inspection contractors, bill between $8,000 and $14,000 a month depending on workload. It appears that Gestim and other contractuals set their own schedules, whereas full-time employees don’t have that luxury.

Hudson’s unionized workers have been without a contract since 2022, yet there seems to be no hurry to sign a new deal despite growing frustration within the union rank and file. Depending on who one talks to, contracting is either more efficient or a waste of money hiring outsiders for work that could be more cheaply done by staff.

Another management letter

Management letters from external auditors became a big deal in Hudson, where letters alerting previous councils to serious financial irregularities were shoved into a drawer at town hall. So it’s not good news when BCGO, the town’s external auditors, listed two significant internal control deficiencies and a number of lesser concerns in their 2023 audit:

— journal entries were not routinely approved, potentially allowing unauthorized entries;

—monthly bank reconciliations showed several months of unexplained discrepancies;

— a new information technology policy didn’t include procedures on how often passwords should be changed or how to make them less vulnerable to hackers;

— the town hasn’t published on the provincial contract-management (SEAO) website a list of contracts under $25,000, nor has it updated calls for tenders once they are awarded;

— no GST or QST claims were filed since July 2022, raising the possibility the town might be unable to recover tax credits.

The SEAO contract-management issue was addressed with the deposit of the overdue report at the March meeting, but in Hudson’s fragile human-resources environment, the letter demonstrates how lapses are inevitable. Was actual harm done? We don’t know what we don’t know.

Flood zones

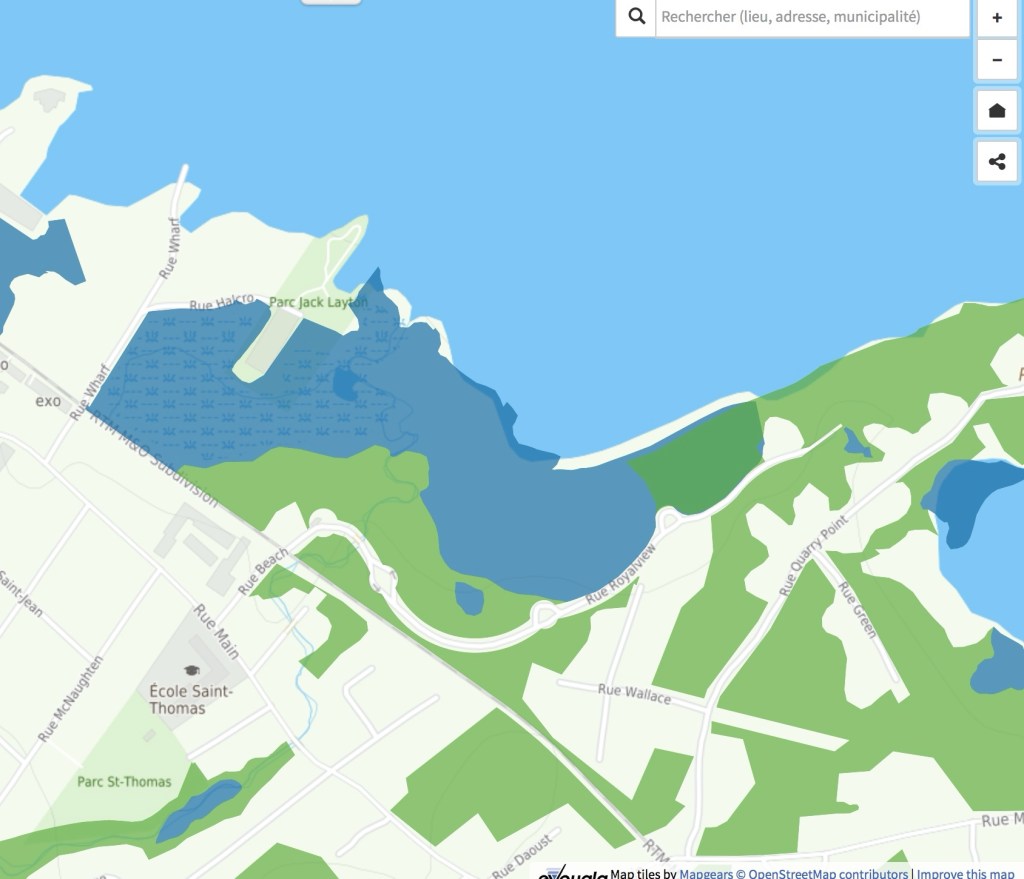

As water levels rise in the Lake of Two Mountains, Hudson’s lakeside homeowners are getting antsy about how the town is dealing with the environment ministry’s revised flood zone maps (geoinondations.gouv.qc.ca).

The revisions raised the number of flood-prone properties in the province from 22,000 to 77,000 and led to generalized panic among waterfront municipalities. In Hudson alone, the number of properties facing some degree of flooding risk jumped from 36 to 61 and the total area affected increased from 96 hectares to 155.

Neighbouring municipalities Rigaud, Vaudreuil-sur-le-lac, Terrasse-Vaudreuil and Vaudreuil-Dorion have thrown their support behind a second petition asking Quebec to delay application of the new maps to satisfy a recommendation from the provincial ombudsperson for a simplified process to apply for a revision. Sponsored by Vaudreuil MNA Marie-Claude Nichols, the Révision de la cartographie des zones inondables petition also seeks to modify the risk assessment protocol and give residents and municipalities options to lower their risk rating. As of March 26, it had 1029 signatures. Signatures close May 19.

A previous petition gathered nearly 2,400 signatures when on Jan. 30, it was killed in committee by the CAQ government. Marilyne Picard, the caquiste MNA for Soulanges whose riding includes Hudson and Rigaud, told Neomedia her government had no choice but to push ahead with the revisions as is, given the increase in catastrophic flooding due to climate change.

Quizzed at the Dec. 16 meeting about what steps Hudson is taking on behalf of the owners of those 61 affected properties, Hutchison said the town’s responsibility is limited to enforcing Quebec’s maps.

The only recourse for those 61 property owners? “Contact the provincial government,” the mayor responded. One gets the impression that Hudson property owners whose residences fall within the environment ministry’s new red zones will have to figure out their financial and legal exposure for themselves.

Baked-in surpluses

Why do Hudson’s budgets increase year over year at more than double the rate of inflation? Since it took office in late 2021, this council has voted to increase cumulative spending by $6.8M — ($10.8M in 2021, $13.7M in 2022, $16.3 in 2023, $16.9 in 2024, $17,687,200 for 2025).

The 2025 budget is the first using the 2025-2027 valuation roll, which raises Hudson’s total worth by 40%, but that only drives assessment-based downloads from other levels of government such as policing and public transport. The 2025-2027 triennial capital investments program (PTI ) wish list accounts for $10.35M over those three years ($5.9M in 2025) but one must seriously wonder how much of that will actually get spent — and on what.

What is unclear to many residents is why the town doesn’t prioritize infrastructure investment. Historically, Hudson’s major discretionary expenses have involved essential infrastructure, such as last year’s $627K upgrade to the Hudson Valleys drinking water network.

Is repaving all of Hudson’s 80-plus kilometres of roads without fixing what’s underneath an essential capital investment? As we learned at one council meeting, 11 kilometres, representing 14% of Hudson’s streets, have been repaved at a cost representing 16% of the budgets for the past three years. At the current rate, it will take four electoral cycles to repave all of Hudson’s streets at the rate of 18 kilometres over four years.

Residents ask me why the repaving program isn’t combined with infrastructure upgrades such as sidewalks, drainage ditching and sewer system extensions — coupled with better policing of failing septic tanks. In a damning January 2012 report on the status of Hudson’s private wastewater treatment systems, consultant Hemisphere concluded that 51% of all septic tanks predate provincial regulations and are at risk of non-conformity; more than 200 installations, representing 11% of the total, pose a significant threats to wetlands, water table and shorelines. To put it bluntly, Hudson’s wastewater treatment stinks.

The four-year push to widen and drain Lakeview is finally about to happen, with a resolution adopted by council at the first meeting of 2025 to authorize the expenditure of $4.532M, a necessary preamble to calling for tenders. The invoices for previous major projects paint a bleak picture of what it really costs. Essential structural repairs, repaving and a sidewalk on Selkirk between Lakeview and Main cost more than $750,000, not including engineering and inspection.

Much of what is contained in the current PTI is wishful thinking, beginning with the decade-long dream of replacing Hudson’s inefficient, decrepit town hall, built as a community centre at the turn of the last century and just reopened after yet another makeshift patch job. Town employees play musical chairs, moving between makeshift offices in half a dozen unsuitable town-owned buildings. The old firehall and public works yard, built on some of the town’s most valuable real estate, remain an eyesore in the centre of town; plans to move Public Works across the tracks next to the sewage treatment plant are on indefinite hold.

Certainly not because the town is broke, which touches on another resolution adopted at the March meeting. Hudson, currently sitting on somewhere north of $8 million in accumulated surpluses (another $1.3M from 2024) has come under the scrutiny of Quebec’s Municipal Commission (CMQ) for how it racks up surpluses year after year.

Hudson was one of three similar-sized Quebec towns (together with Saint-Gabriel-de-Valcartier and Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan) flagged last May for in-depth audits to determine why they were piling up cash reserves instead of providing residents with services, leveraging infrastructure improvements or paying down long-term debt (Hudson’s stood at close to $23M at the end of 2023).

The audit singled Hudson out for special mention on issues dating back to 2013, including:

— taxing property owners before the enabling loan bylaws were approved by Quebec or shifted from bridge financing to long-term debt, then failing to compensate them for the excess collected;

— failing to make clear the funding source for spending bylaws until the end of the fiscal year, long after decisions had already been made;

— shifting funds between earmarked surpluses without enabling resolutions.

Many of the allegations were the subject of previous management letters from the town’s external auditors. The overtaxing of property owners connected to the municipal sewer system has been resolved (the town paid down $585K in long-term sewer debt at the end of 2024), although the overtaxees have yet to be compensated.

At the March meeting, council kept its promise of a response to the CMQ audit by tabling an action plan to implement Quebec’s recommendations. One hopes residents can see the surplus management plan as of the April 7 meeting.

Expertise on call

This council perpetuates the Hudson tradition of hiring outside expertise whenever there’s a decision to be made or defended, like last year’s ill-advised — and ultimately rejected — tax grab to fund greenspace acquisitions.

The 2025 budget earmarks $357,700 for professional services, a $260,000 jump over last year’s line item ($98,400) for inspectors, urban planners, lawyers, engineers, biologists, assessors and other professional service providers.

Monthly disbursements bear out that dial-a-consultant reflex. For example, December’s meeting approved a disbursement of $11.5K to study the cost of moving the Community Centre generator from the front to the back of the building. That doesn’t include moving it, which hasn’t happened yet.

Some, like last August’s $55,000 bill from Habitat/Eco2Urb for an updated conservation plan, are in keeping with the priorities of this and the preceding council. BC2’s $24,000 bill for a parks and greenspace master plan resulted in such decisions as moving the town rink to St. Thomas Park. There’s no followup yet on an $19,000 charge from BC2 for a cost-benefit analysis for the purchase of a lot that would give the town access to Sandy Beach. (More on that below.)

Then there’s the Enclume file. Council paid this strategic-management consultant at least $8,500 to sit in on negotiations with the owner/developers of properties next door to the old Viviry at 498 Main, next to the SAQ at 514 Main and on the site of the old Medi-Centre at 98 Cameron. The town’s goal — to convince the owners to make concessions on what could be built — appears to have had mixed results. At the March meeting, council approved a $32K cash-only parks and greenspace assessment in exchange for greenlighting a previously submitted 20-unit condominium project for 98 Cameron. I was told the project requires no further approvals in order to submit a request for a building permit. Meanwhile, 498 Main is back on the market for $1.8 million, while there’s no word on an already-approved 18-unit condo next to the SAQ. I’m guessing it’s because the developers pushing ahead with their threat to sue the town.

After strangling the Villa Wyman 18-unit continuing-care project with administrivia, this council ended up buying the land from the non-profit and beginning a multi-year process to obtain the funding to do what the original owners had intended at no cost to the taxpayers. Although the town will eventully get its $750,000 back, the project has been taken over by Toit d’Abord, a non-profit regional housing authority to which Hudson will pay an annual assessment.

At the March 10 council meeting, what were supposed to be final draft modifications to zoning bylaw 526 were adopted, subject to public consultation. One revision would have allowed council to exempt any building permit application for a redevelopment project or the intensification of existing activities on a piece of land, from the obligation to to transfer land or pay for park, playground or natural area purposes. At the public consult, residents voiced concern that without guidelines and guardrails, the revision opened the door to a double standard or other abuses. The mayor agreed to further modifications to allay concerns.

RCI freeze ends

The Interim Control Measure was finally lifted this past January, ending a three-year struggle to draft, modify or replace existing land-use regulations, first with draft bylaws 767 and 768 — and when higher levels of government had their say — with replacement bylaws 767.1, 767.2 and 772.

The RCI was adopted in December 2021 as a 90-day subdivision and construction freeze on lots within wetlands and woodlots characterized in the 2020 Eco2Urb conservation study. Residents were sold on the need of the freeze to buy the time to revise Hudson’s planning program.

The delay froze most new multi-unit residential development, including subdivisions approved by previous councils (Willowbrook, Hudson Valleys) and triggered an undisclosed number of lawsuits. In adopting the freeze, Hutchison conceded that hundreds of lots would be impacted, although construction on many has since been approved following third-party analyses of their ecological value.

Originally, the mayor had expressed hopes the RCI could be lifted last August, but short-staffing issues delayed presentation of draft bylaws 767 and 768 until January 2024. (Although not subject to approval by referendum, they required public consultation.)

Those consultations swere carried out over three events in January 2024: open houses Thursday, Jan. 25 and Saturday Jan. 27 and a Q&A Wednesday, Jan. 31. Residents had two weeks to submit their observations and suggestions. Final adoption was scheduled for April 2 before being submitted to the Vaudreuil-Soulanges MRC to ensure they didn’t clash with SADR3, the MRC’s master development plan, by extension, the Montreal Metropolitan Community’s PMAD. The MRC had 150 days to respond.

Bylaw 767 amended sections of existing bylaws without replacing the bylaws themselves. Parts of zoning bylaw 526, subdivision bylaw 527, permits and certificates bylaw 529 and architectural control bylaw 571 were replaced with new definitions and tighter rules on everything from tree protection and replacement to the acquisition and sale of private and town-owned greenspace.

Bylaw 768 imposed tighter development constraints on the four largest parcels of undeveloped land in the urban perimeter: Willowbrook (R-7, R-15); Sandy Beach (R-22, R-24); Charleswood/Côte St. Charles (R-55) and a site on the north side of Main Road opposite Somerset. Regarding the proposed 214-unit Sandy Beach development, 768 held out the possibility the town could approve single-family, semi-detached two and three-family dwellings with an gross density of 17.5 to 35 units per hectare.

For both R-55 and Sandy Beach, 768 had proposed the creation of residential sectors where people would not need cars. “The comprehensive development plan […] is close to the village core and at a short distance from the Hudson train station…Therefore particular attention must be paid to reducing facilities favouring automobile use, both in housing offerings and outdoor facilities.”

Neither bylaw received MRC approval, forcing the town to split 767 in two. Bylaw 767.1 contained only those elements that passed the MRC, while 767.2 contained revisions to bring them into concordance with the MRC’s master plan and the CMM’s PMAD. Major changes to 767.2 reduced the impact of conservation-area designation in a dozen zones and added requirements for tree felling in wooded areas and forest corridors identified by the CMM.

Bylaw 768 required extensive surgery in order to conform. Rather than rewriting it to fit, the town replaced it with a new bylaw, 772, which exempted part of Willowbrook and the site of the proposed seniors campus off Charleswood. The new bylaw also increased average densities in parts of the urban core and added traffic-calming, housing diversity and agricultural-use criteria. The changes were presented at a public consultation in November and approved by the MRC on Jan. 15, 2025, when Hudson’s RCI was lifted.

Sandy Beach

Elected on a platform which included the conservation of Sandy Beach, the current council will have achieved its goal without dipping into the town’s accumulated surplus, thanks to the Montreal Metropolitan Commmunity’s 2022 RCI which will remain in effect for an indefinite period.

For beach lovers, the downside is that access will remain closed indefinitely. At the December meeting, Hutchison made it clear the footbridge connecting Jack Layton Park and Sandy Beach would not reopen, given the challenge and cost of authorizing an alternate route on public land. Instead, the town’s efforts will focus on acquiring public access from the eastern end of Beach Road.

Pressured by buy-the-beach activists to commit to the purchase of all or part of Sandy Beach, the mayor’s response made it clear the town will maintain a neutral stance. “We must continue to be very pragmatic,” she told Save Sandy Beachers at the October meeting.

When one questioner insisted it was council’s job to front a fundraising campaign, the mayor responded by asking whether they had set up a legal entity or fundraising structure.