This is my submission to the public consultation (Wednesday, Oct. 23/24) on the Town of Hudson’s proposed parks and greenspaces policy.

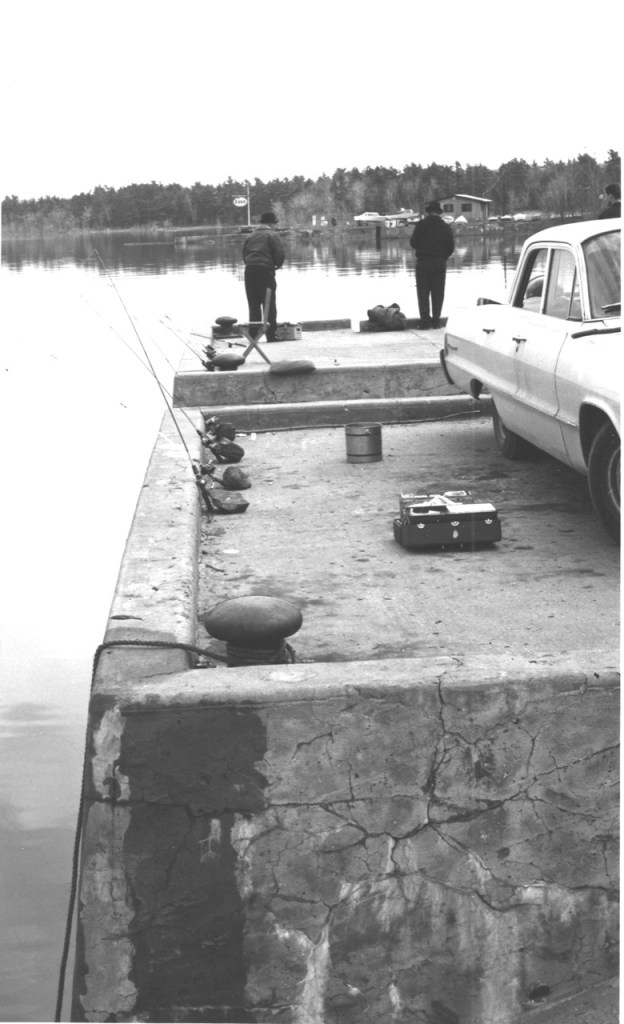

With this past week’s indefinite closure of Hudson’s historic steamboat landing at the foot of Wharf Road, residents and visitors lose another window on the Ottawa River. I don’t hold out much hope that it will ever reopen, given the extent of its deterioration.

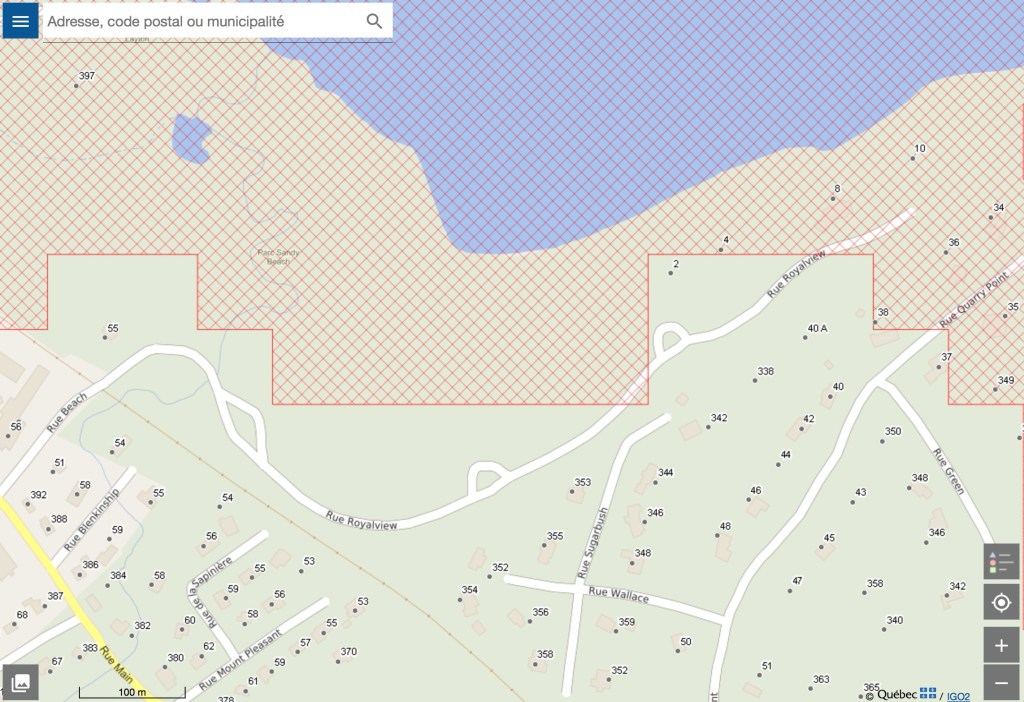

The preservation of a crumbling 19th-century town wharf may be no big loss for some, but this indefinite-closure thing is becoming a trend, what with the posting of Sandy Beach and now the barricading of the footbridge which used to be the sole public access. Unless you’re a Hudson Yacht Club member, the only remaining public access to Hudson’s 14 kilometres of waterfront is via Jack Layton and Thompson parks.

Hundreds of boaters depend on the JLP launch ramp, dock and the nearby cove. The dock was widened under the previous administration, but the ramp hasn’t changed since Dudley Reid and Lucien Mallette opened a marina on the location of the massive Wilson Company icehouse where Canadian Pacific once loaded blocks of ice from the Ottawa River into reefer cars to transport perishables in the time before refrigeration.

Those of us who use the ramp are immeasurably grateful for the privilege. (Use of the ramp is free because the last council determined that it doesn’t conform to standards that would justify charging people. Instead, we use it at our own risk.) It’s self-policing; people wait their turn regardless of the size and value of their craft.

Hudson worked out a deal with St. Lazare that would allow residents of both municipalities a free annual permit and nearby parking privileges. In return, Hudson residents enjoy free access to Les Forestiers and its well-maintained ski and walking trails. For $125 a year, Vaudreuil-Soulanges residents can buy the right to park nearby; for everyone else, it’s $250 unless they choose to park free at the snow dump, a five-minute walk. Use of the park is free for all.

Our council looked at Thompson Park as an alternative to JLP for non-motorized craft. The problem is getting one’s boat to the water’s edge, a football field’s distance and a steep hill away, most of it within the 100-year floodplain. We had serious doubts the environment ministry would approve construction of a road, a parking lot near the water and a dock. As well, the sandy shoreline quickly grows an impenetrable thicket of aquatic vegetation that would require regular cutting. We agreed it wasn’t a sustainable solution.

We took a closer look at the former marina. If mayor Liz Corker’s council made the decisions necessary to begin its transformation, the artistry of landscape architect Brian Grubert and stonemason Bob Houghton turned it into a riverside gem while preserving its vocation as a boat launch with public parking.

How could we expand its use? Council mandated the parks and recreation department to come up with a survey detailing how other waterfont municipalities manage access to users and residents. A local business proposed a boat rental kiosk similar to the operation at Vaudreuil-Dorion’s Valois Park. Our regional Caisse Desjardins offered to fund a separate launch at the east side of the park where kayakers and paddleboarders could launch and recover their craft without having to queue up with the powerboaters.

A council majority ended up rejecting all suggestions, based on the probability that the environment ministry would probably says no. End of discussion.

When news broke of the wharf’s closure, Bob Houghton had an interesting suggestion. Why not continue what Mother Nature began, knock down the crumbling concrete and backfill with boulders as he and Grubert did with the icehouse site? It would allow the creation of a waterfront promenade on the footprint of the original wharf, typical of the commonsense simplicity that once graced Hudson’s approach to problem-solving. The environment ministry could hardly reject a project built on what was.

But would residents support a relatively low-cost proposal that would give us another window on the lake when previous plans to repurpose the wharf went nowhere? A 2019 a Canadian Coast Guard proposal would have seen the wharf turned into a much-needed base on the Lake of Two Mountains. Wharf Road residents objected, council was wary of hidden costs to taxpayers and the Coast Guard went elsewhere. Last year, I wrote about how one of the subcontractors for the new Ile aux Tourtes bridge proposed to assemble components in the town snow dump, transport them to the wharf, and ship them to the site by barge (www.thousandlashes.ca/23/06/06). In exchange, the town would get a rebuilt wharf.

The plan was scrapped because the wharf was too far gone.

Meanwhile, other municipalities recognize the social and economic value of accessible public waterfronts. Pointe Claire has its waterfront walk and pier where the Edgewater Inn once stood. Ile Perrot transformed a crumbling seawall into public access. Les Cedres and Pincourt revitalized their small-boat launch facilities. Oka added small-boat docks to its well-maintained public wharf opposite the Hudson-Oka ferry landing. It’s not the cost, but the political vision required to see the value in expanding public waterfront access.

Why should Hudson maintain, even increase public access to its waterfront?

Boat ownership is quickly moving away from parking one’s boat in a yacht club or marina. It’s both generational and about how people want to spend their money. Paddleboards, canoes and kayaks are relatively inexpensive, easily moved on rooftop racks anywhere with public parking where they can be launched and hauled out. It’s also a a matter of freedom; boats on cartops or trailers and in pickup beds can be stored on one’s property (with some bylaw exceptions) and driven to any body of water with a public ramp.

In light of the exploding interest in low-overhead boating among enthusiasts who may live nowhere near the water, the Montreal Metropolitan Community is encouraging riverfront municipalities to clean up their shorelines and add launch facilities, preferably with non-motorized boat rentals and maps of local waters registered with the MCC’s aspirational Blue Corridor, the paddle/oar community’s vision of a network of boating routes through the hundreds of islands surrounding Montreal.

At the same time, more and more waterfront municipalities are restricting access to their launch facilities in response to residents complaining about the small-boat invasion. It boils down to making one’s facilities either pay per use or open only to passholders. Like Hudson, a handful offer launch facilities open to all with restrictions on parking, but all draw the line at overnight camping. I’ve seen waterborne travellers stealth camping at Hudson’s Thompson Park and Lachine’s Stoney Point and there are safe places to pull out if one knows where to look, but municipalities see these outliers the same way they look on homeless encampments — with suspicion.

The problem with nostalgia is that most Hudson residents have no memory of what was. As kids growing up in Hudson’s waterfront, we grew up building driftwood rafts and poling them with saplings. As we grew older, we acquired our first boats and roamed further afield to Oka Beach and the sandbars off Carillon Island. Most of us learned to swim off whatever wharf or dock we had access to.

Hudson’s public access to these simple pleasures is under increasing pressure from too many conflicting demands. Rather than accepting their closure, we should be investing in maintaining, upgrading, expanding and exploring alternatives.