The Town of Hudson isn’t using its multi-million-dollar surpluses and cash reserves to best advantage, according to an audit of its fiscal procedures by the Quebec Municipal Commission (CMQ), the municipal affairs minister’s governance arm.

Worse, says the CMQ, there has been an historic lack of accountability and followup when it comes to knowing how tax dollars are being spent until it’s too late to do anything about it.

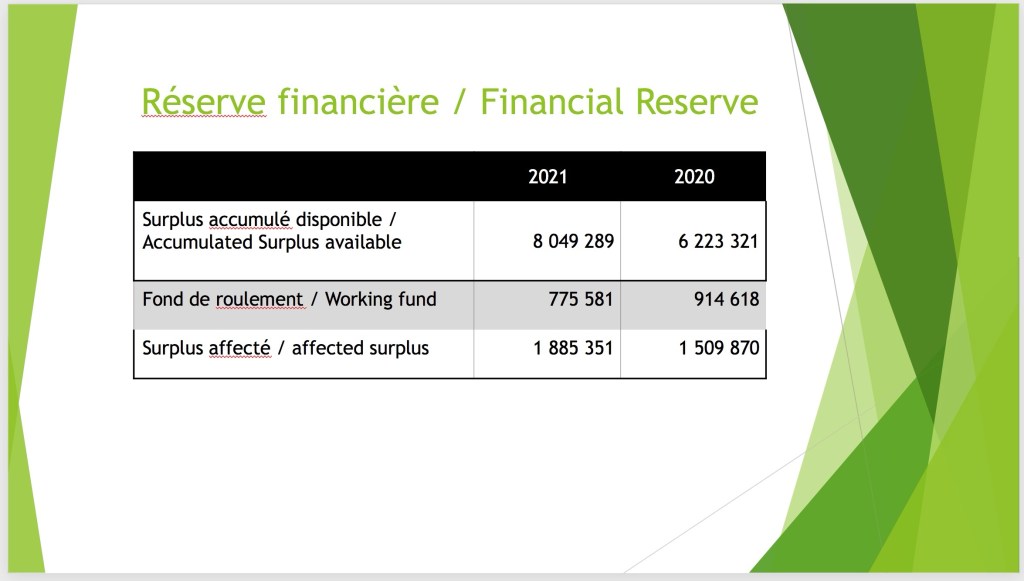

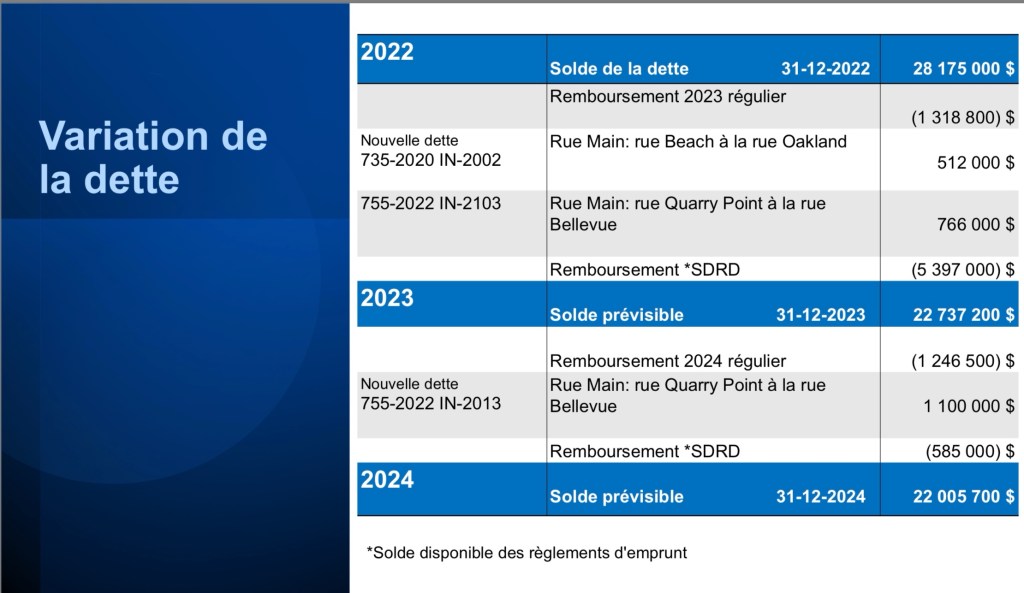

With an accumulated surplus in excess of $8M and long-term debt of close to $23M at the end of 2023, Hudson was one of three similar-sized towns (with Saint-Gabriel-de-Valcartier and Saint-Roch-de-l’Achigan) flagged last May for in-depth audits to determine why they were piling up year-over-year cash reserves instead of providing residents with services, leveraging infrastructure improvements or paying down long-term debt.

In Hudson’s case, the municipal affairs ministry had already noted the town’s total debt load per resident — $1.85 per $100 evaluation — because anything over $1 per $100 is considered high.

Posted this morning (Tuesday, Feb. 27) on the CMQ website, the audit will be be tabled at the March 4 council meeting. On March 11, financial consultants RCGT (Raymond Chabot Grant Thornton), mandated in 2023 to prepare the Town’s financial portrait and projection for 2023 to 2028, will present their report to residents, a fact the CMQ audit took into consideration.

Most of the 31-page document applies to all three municipalities, beginning with the observation that surpluses and reserves are not well integrated with the planning process. Councils and staff didn’t prioritise how or where the monies should be spent. Triennial investment plans (PTIs), adopted along with annual budgets, were concocted with minimal public input and didn’t conform to Cities and Towns Act requirements that funding sources be included. Although councillors discussed how PTI projects were to be funded, this wasn’t shared with the population, leading to a possible transparency issue with residents.

Without transparency, there can be no accountability, the report continued. “Without the accountability that the citizens have a right to, a municipality can’t guarantee sustainable finances.” Without sustainable finances, a town makes itself vulnerable to unforeseen situations.

The CMQ’s second observation: none of the three municipalities has a formal framework for how they earmark their surpluses and cash reserves. In the case of Hudson and St. Gabriel, a lack of followup mechanisms means the management of these surpluses and reserves is left to individuals, with no guarantee the funds will be spent according to the town’s long-term strategic plan — if there is one.

The audit singles Hudson out for special mention on issues dating back to 2013, including:

— taxing property owners before the enabling loan bylaws were approved by Quebec or shifted from bridge financing to long-term debt, then failing to compensate them for the excess collected;

— failing to make clear the funding source for spending bylaws until the end of the fiscal year, long after decisions had already been made;

— shifting funds between earmarked surpluses without enabling resolutions.

Most of the allegations have already been the subject of management letters from the town’s external auditors. The overtaxing of property owners connected to the municipal sewer system was dealt with by the previous council, although the victims were never compensated.

“The report makes clear to me that the CMQ is prepared to blame the past and point to the bright future,” said a source familiar with the file. “It is positive [and] points to a future plan. Still curious what that is.”