They are a bunch of amateurs,” Hudson mayor Chloe Hutchison tells 1019 Report’s Brenda O’Farrell. “Put it in the hands of people who can get it done.”

An unfortunate choice of words in a town which depends on amateurs and volunteers for a wide range of activities and services, many of them taxpayer-funded. Was it meant to be off the record? Not for attribution? Or will the mayor insist yet again that she was taken out of context?

Whatever, the mayor’s gratuitous insult appears to have been directed at the Villa Wyman’s board of directors, who voted earlier this month to abandon plans for an 18-unit assisted-care senior’s residence in Hudson’s downtown core after having been jerked around by the current council for the better part of two years.

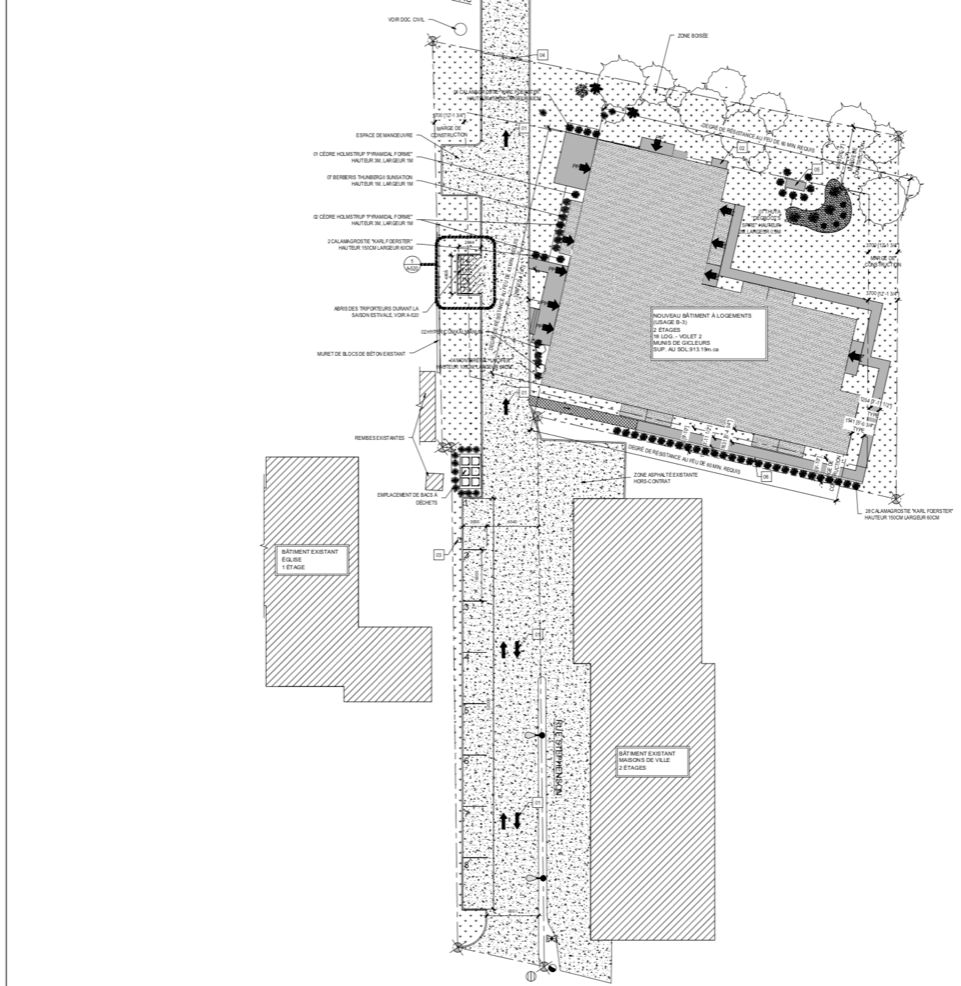

Although the Villa Wyman project was eventually approved by the current council a year ago (Nov. 7/22), the town continued to demand architectural, parking and landscaping modifications, each one of them pushing back the construction start date by the time it took to work its way through the urban planning approval process.

The board’s Dec. 7 decision to terminate the project followed council’s refusal to grant the project a minor derogation to accommodate an encroachment on the parking lot shared with the former Wyman Memorial church, now a Sikh temple. “It was less than three feet,” board member Diane Ratcliffe told me.

A municipal derogation was required because the temple’s administrators, after months of delay, refused Villa Wyman’s request for a legal servitude.

The irony in the mayor’s bunch-of-amateurs comment is that it was Villa Wyman’s architect —a professional — who failed to notice the encroachment. Nor were they alone in missing it. Encroachments are highlighted in surveys as well as in deeds of sale, which involve realtors, surveyors, notaries and urban planning departments.

My point is that a raft of professionals were involved in the eight-year journey planning this $8 million project. Municipalities, Hudson included, routinely approve minor derogations for exactly these reasons.

Earlier this fall, an alarm bell rang when the mayor, asked about the project’s advancement, said this council would not approve a derogation. I took it as a warning that unless the various actors in this slow-mo farce could come up with an alternative, the Villa Wyman project was doomed.

Those of us who have followed its evolution since it was introduced as a rezoning bylaw during the Prévost administration know it was crippled from the outset by a slew of factors. Its location, on the south end of the Wyman parking lot behind Stephenson Court, was less than ideal.

Residents, including Hutchison, fought the rezoning bylaw before a provincial administrative tribunal, which ruled the town was within its powers.

Throughout the process and even now, board members have refrained from attacking the administration, but when asked if they might reconsider their decision, the answer remains a firm no.

The board isn’t looking at doing anything else in the future, Diane Ratcliffe told me this past week. “If we were to go forward, we would be getting into the hard part — construction, where decisions have to be made quickly.”

In the end, it became a matter of whether the board could trust the current council not to sabotage the project, then blame it on them.

“In any endeavour you need partners. The town told us ‘Do not come to us for a request for a derogation’ […] the Sikhs are not willing to work with us. Without approval, support or partnership we didn’t have the stomach to go forward.”

The next phase begins with cancellation of the mortgage associated with the project, Ratcliffe said. “The SHQ (Société d’habitation du Québec) will help guide us through the process of rolling it back.”

Once costs already incurred are paid out, the rest of the $4.2 million in federal and provincial funding will be returned.

As for the now-empty lot, the mayor indicated at the August 7 council meeting that the town could use its power of pre-emptive rights to put a freeze on the land for as long as 10 years. Whether or not the town would be forced to buy it at some future date will depend on recent changes to legislation giving Quebec municipalities greater powers to expropriate land.

(https://lp.ca/ekojcV?sharing=true)

Ratcliffe is hopeful that the board’s work won’t be wasted. “I gather that there is a non-profit group created this past February, Toît d’abord, that has been set up, with (St. Lazare mayor) Genevieve Lachance president of the board of directors […] Chloe, chairing the MRC regional housing board, suggested we get in touch with them.”

“We are going to look into it with Manon Leduc, our point person and DG of Groupe des ressources techniques du sud-ouest, our staff person who steered us through the entire process,” Ratcliffe added.

Leduc’s professional track record includes the 82-unit co-op apartment block in Pincourt’s Pointe-a-Renard sector. “She has contacts with similar associations that exist everywhere in Quebec.”

Ratcliffe’s harshest words directed at the mayor and council? “It would be really nice if they made their intentions clear. If they had a plan for the village core, they should share it.”

A heartfelt apology is in order, Madam Mayor.