On Thursday, Feb. 16, Hudson residents will learn how Mayor Ed Prévost’s administration proposes to allow Hans Muhlegg to develop Sandy Beach and what it will mean for the thousands who take advantage of Hudson’s public window on the Ottawa River.

This latest public consultation will be Muhlegg’s fourth kick at the Sandy Beach can, each under a different mayor. Steve Shaar cut a rezoning deal approved by 72% of the vote in an October 2001 referendum. Elizabeth Corker’s administration adopted the attitude that environment ministry hurdles would stall the project until Muhlegg gave up and agreed to a sewered project of 70 single-family dwellings. Michael Elliott did his utmost to move the project forward but couldn’t get the pieces in place before his time ran out.

Hudson’s current administration appears to be in a hurry to submit a revised development plan I suspect may not be subject to approval by referendum. I’ll get into that later on.

This is an old, old game, this dance between the town and a succession of Sandy Beach owners. In the ‘60s the Blenkinship family was ready to sell the 60 acres to the town for $235,000. A dozen years later, Claudette Boyer offered it to the town for the taxes owed before selling it to Muhlegg’s company for $450,000. Muhlegg himself has expressed his ambivalence at seeing Sandy Beach developed. I’ve come to believe the people most interested in seeing it developed and the least interested in seeing it remain greenspace are the past 60 years of mayors and councillors.

Sandy Beach hasn’t changed much since the retreat of the glaciers. Algonquin tribes fished salmon, muskie, perch and walleye in its shallows and sheltered among its ancient pines and hemlocks along the same shoreline where toddlers splash.

New France brought the fur trade to Sandy Beach in the form of a trading post and gristmill. Historian Maben Poirier once showed me the massive square-cut stones and remnants of the millpond where pre-Conquest entrepreneur Marcellin Farand dit Vivarais built his mill on the creek that bears his name. I’ll post an interesting sidebar on Maben’s musings.

The Viviry River and Parsons Point created Sandy Beach. Swift-flowing and clear, the Viviry drains a 114-square-kilometre watershed with its origins in the spring-fed bogs at the top of Côte St. Charles. In its rush to join the Ottawa, the Viviry transports tonnes of fine sand from St. Lazare, only to drop its load as it runs into the slow-moving river. Over the centuries the sand from the Viviry has mixed with the sand from the Ottawa’s long fetch to form a perfect half-moon alluvial delta all the way to Quarry Point.

Sandy Beach is Hudson’s last remaining window on the Ottawa River, the last reminder of Canada’s steamboat era. During the Depression, Canadian Pacific ran trains directly to Sandy Beach, filled with inner-city dwellers yearning for escape from Montreal’s heat. The Blenkinships, who owned it back then, charged a quarter per car to cross the culvert bridge where Vivaris’s dam once stood. Old timers recall the beach, snack bar and store with the excitement of teenagers. It sounds like a magic place, which of course it still is.

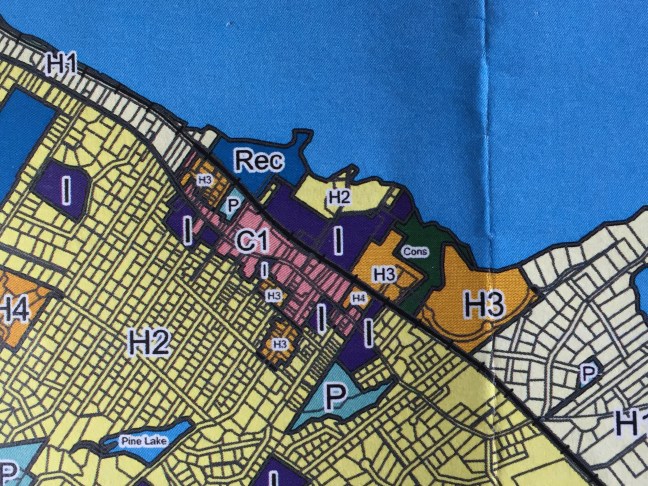

Development was always an option. The 60-acre parcel was zoned for roughly 40 single-family dwellings on 40,000-square-foot lots, but the cost of subdividing and servicing that part of Hudson made it financially unattractive until Hudson adopted a new master plan in 1994. Nicanco’s holdings were included in PAE 1-C, a new zone which would permit condominiums, semi-detached homes and townhouses.

The current discussion had its beginnings almost 20 years ago and as you’ll see, has been shaped by unintended consequences.

In a March 25/98 front-page story, the Hudson Gazette reports:

The fate of one of Hudson’s last remaining pieces of waterfront greenspace depends on whether there’s a market for single-family homes on the 60-acre site – or whether the owners will be permitted to rezone the area for multi-family dwellings.

The Hudson Gazette has learned that representatives of the owners of Sandy Beach met two weeks ago with Hudson Mayor Steve Shaar and others to discuss the possibility of zoning changes for the environmentally sensitive area.

[…] Planning Committee chair Elizabeth Corker believes a development of single-family homes on the property would not be economically viable.

“At least 10 per cent of it is in the flood zone,” she said. “The developer has to give the town 10 per cent in greenspace.” Another 15 per cent would be required for roads and other infrastructures, meaning there would probably be room for about 30 homes.

April 8/98: Citizens petition for unfettered access to beach. Organizers Shawn Murphy and Heather Cockburn point out the town has the right under PAE 1-C to claim as greenspace any 10% it chooses and notes that 10% of the 60 acre total lies in a flood zone.

April 15/98: There’s no rush to buy Sandy Beach, Mayor Shaar tells residents at the monthly council meeting. He accepts a 250-name petition demanding that the 10% greenspace allocation be in the form of beachfront stretching from the tip of Quarry Point to what is now Jack Layton Park.

May 13/98: Shaar tells the monthly council meeting he’s to meet with Nicanco May 26 to discuss buying all or part of Sandy Beach. Asked about Muhlegg’s offer to help find funding to purchase the property, Shaar said Nicanco’s offers were vague and the letter disjointed, as was a followup letter. Shaar reads Muhlegg’s latest letter to the meeting expressing dissatisfaction with the lack of an offer from the town and asking for a meeting to discuss the company’s proposals. The mayor concludes by saying negotiations won’t go far with a $6 million floor price.

The story quotes Muhlegg saying formal and informal meetings on the future of Sandy Beach have been going on for seven or eight years, leading some residents to wonder whether promises had been made when the 1994 master plan was adopted.

May 27/98: Corker challenges Nicanco’s asking price, wondering how a 60-acre property with a municipal evaluation of $2.37 million can be worth $6 million when half will be required for infrastructure or undevelopable.

July 6/98: Nicanco bars public access to Sandy Beach and posts a security guard at the Beach Road entrance. Nicanco’s Robert Sabbah says the fence is necessary to prevent vandalism. Shaar calls it a pressure tactic. The town, he says, is not prepared to make wholesale changes to the PAE, which poses no barriers to development.

July 29/98: Tempers flare at Nicanco’s Sandy Beach information meeting as residents shout down Muhlegg’s presentation of his proposed Pine Beach Village. The development would include a restaurant-inn, 60-suite seniors residential complex, 22 villas, 12 semi-detached units, 60 townhouses and a fitness centre with an indoor pool. Nicanco claims the development will generate $400,000 a year in taxes.

Residents zero in on the lack of public beach access. Although the proposal includes 9,000 square metres of greenspace, public beach makes up 125 square metres and is located in a wetland. Muhlegg claims wetland can be transformed into beach. Not everyone is opposed; resident Peter Johnston calls it a well-thought-out project that should nt be condemned because people want to walk their dogs.

Aug. 5/98: Mayor Shaar later says Nicanco’s plan was rejected because the comprehensive development program (PAE), doesn’t permit commercial development. Nor is the town happy with the greenspace being offered. The beach property offered isn’t a beach. At $6 million, the town isn’t buying and Hudson historically doesn’t expropriate, he adds – so the ball is in Muhlegg’s court. Nicanco complains the town is asking for 42% of the 60-acre total. Not true, says Shaar. “They’re including roads, flood zone, greenspace – things that are not part of the calculation.”

Sept. 23/98: Nicanco to present new proposal for Sandy Beach. The story quotes Robert Sabbah, director of business development for Nicanco Holdings, Hans Muhlegg’s brother-in-law. It’s the first sign of a break in the impasse that began with the beach closure.

Oct. 13/98: Discussions between Nicanco and the town continue. The new proposal would include an integrated project with a large building with full services.

The rest of 1998 and all of 1999 passes without public announcement. Then, on Feb. 16, 2000, Hudson residents learn that PAE 1-C is being rewritten to allow a mix of housing. In April, the town planning advisory committee recommends council approve Nicanco’s latest proposal. On May 24, the Gazette reports Nicanco’s fence has been removed in a number of places to allow free access to Sandy Beach.

Meanwhile, events were quickly overtaking Nicanco’s development that would change Hudson forever.

In June 2000, the town awards a contract to the consulting engineering firm LBCD for a feasibility study for a sewage collection and treatment system for Hudson’s downtown core. No fees are payable unless the town receives federal and provincial grants. (In February 2001, LBCD’s mandate is extended to Como’s Bellevue-Sanderson sector.)

Oct. 11/00: Town, Nicanco close to deal. Beach access is the major sticking point.

Dec. 13/00: LBCD submits sewer study. Estimated cost: $6-9 million. (Actual cost: $16M)

Feb. 14/01: Town, Nicanco reach agreement in principle. The developer will give up 20 per cent greenspace, or 12 acres – twice the required allotment.

March 12/01: Town holds public consultation on two rezoning bylaws that will allow mixed-density residential development on Sandy Beach. Fifty residents attend. Bylaws create three zones. R-6 (11.6 acres), the closest to Quarry Point, would allow five single-family residences on 40,000-square-foot waterfront lots. R-7 (23.65 acres), the largest sector, would permit four units per hectare, equivalent to 25 single-family units or 95 townhouses. R-8 (10.6 acres), across the tracks from Manoir Cavagnal and to the west of the Viviry footpath, would allow any combination of 12 single-family dwellings, 40 multi-family units and 50-door seniors residence with a maximum height of 42 feet – three storeys.

May 16/01: Town, Nicanco agree on larger setbacks to create wider buffer zone between the new development and residents on Wallace and Sugarbush.

The estimated cost of LBCD’s sewage project rises to $9.4 million, 85% covered by grants.

May 24/01: Two dozen people attend public consultation on bylaws 408 and 409, modifying zoning bylaw 321 and subdivision bylaw 323.

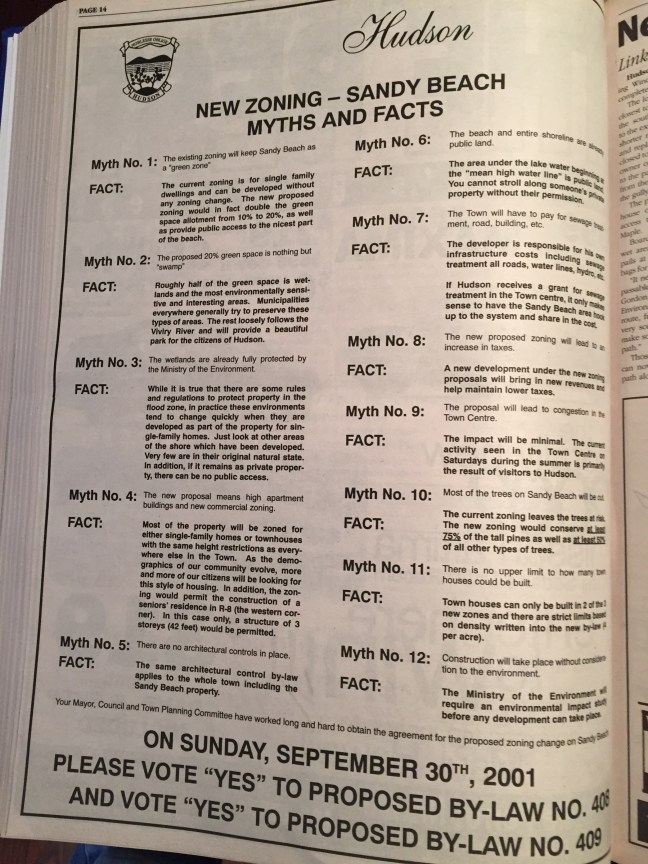

The 54-acre development would preserve 75% of the pine forest and 50% of all trees.

In exchange, the town gets a right of way (ROW) to 1,186 feet of beach, beach access and 11 acres of greenspace.

Most of those in the room oppose the zoning change. They argue that most of Nicanco’s 20% greenspace allocation is already protected wetland or flood zone. Quarry Point environmentalist Kathy Conway asks what happens to the deal if the environment ministry doesn’t approve the project.

That’s our problem, Nicanco’s urban planner Marc Perreault tells her. It proves to be prescient.

Mayor Shaar tells the crowd the project would add a maximum of 150 residential units to the town and reminded everyone the town is facing a $9.4 million sewage system bill. The project is unrelated to the sewage system, Shaar adds – but provision should be made for connecting the Sandy Beach development.

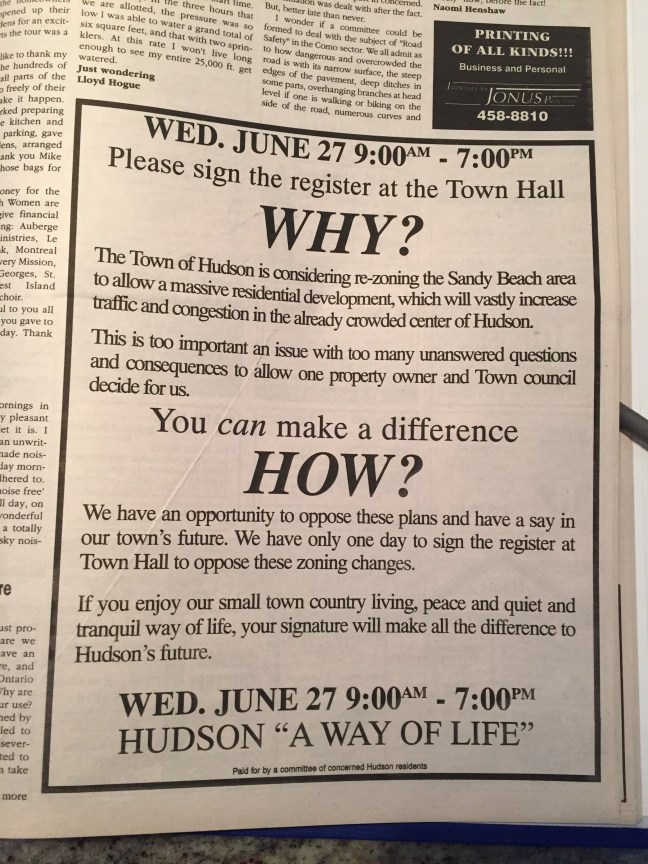

May 30/01: Council tables notices of motion of both zoning bylaws. Residents of contiguous sectors R-1, R-2, C-2, Y-1 (comprising most of Hudson) are eligible to sign a day-long register. 374 signatures are required to force a referendum.

June 27/01: Nicanco’s Marc Perreault warns there will be no further public access to Sandy Beach if the proposed rezoning is rejected.

July 4/01: 444 residents sign the register, 70 more than required to force a referendum.

July 11/01: Council indicates it will withdraw the proposed zoning rather than forcing a referendum. Nicanco is said to be ready to proceed with single-family dwellings.

Aug. 8/01: Council reconsiders, schedules referendum for Sunday, Sept. 30.

Sept. 5/01: Town, Nicanco hold open house to explain the project. The open house launches a massive ad blitz extolling the virtues of Nicanco’s project and downplaying the negatives. Opposition is divided and has difficulty getting its message out. Other projects, like Whitlock West and a proposal to run an access road between Highway 342 and the Oka ferry, fragment those who might otherwise oppose Sandy Beach development. A powerful argument in support of the project is the need to widen the user base for the coming sewer project.

Sept. 30/01: Both rezoning bylaws pass easily. Just 862 of 3,418 eligible voters vote 72% in favour of the project.

From that day on, nothing goes according to plan for Nicanco. Four years after residents approved the rezoning, the 150-door development has seen construction of a single home on one of the five R-6 lots.

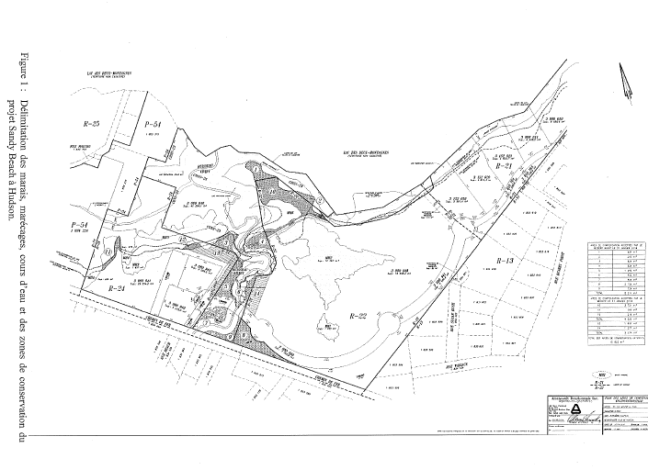

Under Quebec’s Loi sur l’environnement, regional environment ministry inspectors make the determination whether a proposed subdivision requires further study. Their decision is based on acquired data, such as satellite mapping and a basic knowledge of the local topography. Sandy Beach, with a checkerboard of sensitive wetlands, flood zones and ticked all their boxes.

Two more years will pass before Nicanco provides the ministry with multi-season flora and fauna studies needed for authorization to extend Beach Road to the far end of the proposed development. More time is spent fighting the town for the right to service the five lots on Royalview via Sugarbush. At one point, it looked like the only house in the entire project would not be issued a certificate of location because it was located on a private road. Normally, a municipality takes over ownership of a subdivision but Hudson balked until Nicanco agrees to foot the bill for sewering the entire project. To this day, Beach is a private road, while at the far end, Royalview is public.

Dec. 7/05: Hans Muhlegg blames delays on “unplanned and unexpected development constraints.” Asked how a third party would interpret this, he responds: “It’s disguised expropriation.”

Worse, the environment ministry determines that a 1.5-hectare wetland in the middle of R-7 could not be filled in, leaving Nicanco’s largest sector with a money-losing hole in the middle. (It wasn’t until the 2012 passage of a Quebec law allowing developers to backfill a sensitive wetland by trading it for a protected wetland of equal or superior quality in the same watershed that Nicanco could proceed.)

March 30, 2011: Hudson mulls wetland swap to revive Sandy Beach project

How far should the Town of Hudson go in helping developer Nicanco revive the moribund Sandy Beach subdivision to add users to the new municipal sewer system?

Nicanco president Hans Muhlegg is asking the town to sign off on a deal that would protect a parcel of wetland the town already owns in exchange for allowing development of a five-acre wetland in the heart of his 56 acres.

Regional environment ministry officials confirmed last week they’re studying the proposed land switch to determine whether it falls within their land-trade parameters. Under controversial Ministry of Sustainable Development, Environment and Parks (MDDEP) guidelines, developers can ‘buy’ the right to develop wetland by acquiring wetland of equal value in the same watershed.

But Muhlegg isn’t interested in putting more money into the project, says Hudson mayor Michael Elliott.

“His request has simply been ‘will the town help me by freezing a piece of land you already own’?” Elliott explained prior to meeting with Muhlegg and his team last Tuesday. “In other words, to take a similar wet zone which we [already] own opposite the treatment plant, that we already have a court order telling us we can’t do anything with, and rezone [it] to be a sensitive ecological area.”

Nicanco already has the right to develop Sandy Beach, thanks to a 2001 zoning bylaw approved by a majority of residents. The plans call for a mix of single-family, semi-detached and seniors’ residences — all connected to the municipal sewer system.

But by the time he was ready to develop, MDDEP had changed the rules. “Part of the problem is he didn’t move quick enough,” Elliott said. “He should have moved eight or nine years ago for him to get his dispensation.”

Development means an end to unlimited public access to Sandy Beach, but that was already established in the 2001 zoning bylaw. The public will have access to roughly 11 acres, including 720 feet of shoreline — twice the mandatory 10 percent greenspace allowance Nicanco had to give the town.

Last week’s meeting with Muhlegg and his lawyer and biologists was to establish whether the five acres in the middle of the proposed development is as environmentally sensitive as MDDEP’s biologists say it is. The town has asked McGill biologist Martin Lechowitz to go over the data from both sides and advise the town’s environment committee, which will make a recommendation.

The mayor admits he’s torn between seeing more users on the sewer system and protecting every possible inch of Sandy Beach.

“I don’t particularity want to make that decision whether the town should help him,” says Elliott. “As far as I’m concerned the town lost the beach 25 years ago when we could have had it for $235 000.”

Even if the wetland swap is refused, it’s not going to halt development, Elliott points out, “but it will change his drawings where buildings are going to be.”

Both the mayor and town planning committee chairman Rob Spencer see it as an chance to revive an $80 million project while widening the town’s tax base. “The sewage treatment plant was designed to take it,” says Elliott. “I think it’s a win win for the town.

He pointed out that Muhlegg has already given the town more than twice the amount of greenspace required by law. “The decision has already been made to develop the bloody place, it was zoned for development we agreed to that years ago. so all we would be redoing is rezoning a piece of land we can’t do anything with anyway and we own.”

Since that was written, Muhlegg has satisfied the ministry’s wetland trading requirements by renegotiating the conservation zone with the town. The latest map shows alterations to the green corridor cutting across R-7. It also indicates a reduction of beachfront to the east of the access servitude from the end of Beach Road.

None of these revisions have come before public council meetings although they have been discussed by members of TPAC. At worst, say concerned residents, the Prévost administration will present residents at the Feb. 16 meeting with a revised Sandy Beach development proposal limiting beach access while dramatically increasing the number and density of residential units.

Why would council be in a rush to get this done? One theory suggests it’s because neither Nicanco nor the town want to find themselves on the wrong side of Bill 102, a top-to-bottom rewrite of Quebec’s 40-year-old environmental protection act. As of last week, the draft bill was in legislative committee undergoing a clause-by-clause study and could be ready for adoption before the June break.

For Nicanco and this administration, the major differences in the rewritten act are its new transparency and public consultation requirements. For that reason alone, I wonder whether the proposal being presented Feb. 16 will attempt to replace Sandy Beach’s PAE designation with a Plan particulier d’urbanisme, or PPU. Although the change would require ministry approval and consultation, it would no longer be subject to referendum.

For Hudson residents, the question we asked 60 years ago, 50 years ago, 20 years ago is the same question we’re asking today. Is Hudson better off owning Sandy Beach or seeing it developed according to a plan we can agree on?

If you were asked that question tomorrow in the form of a referendum, which way would you vote?

People ask me what Sandy Beach is worth. I have no idea. Once it was $235,000. Today, it’s $23.5 million. Muhlegg has come up with so many figures over the years I don’t think he knows what it’s worth to him.

Muhlegg and I have known one another for these 20 years but I can’t say I understand him.

We’ve sat through innumerable council meetings and public consultations together. I’ve spent hours in his Pointe Claire office and over lunch, listening to him obsessing on his favourite topic: Sandy Beach. He sees it as a jewel, a place of rare beauty that should be preserved in its natural state. He’s on record as having offered the town help in obtaining funding to buy Sandy Beach and suggested that his company might be able to help finance the acquisition. Yet he’s a shrewd businessman, making his fortune developing far-flung parts of the world and investing in highly speculative ventures – prize fighters. He’s a fighter himself, a lung cancer survivor.

If I was to venture a guess, I would say Hans Muhlegg’s perfect Sandy Beach deal would have all 60 acres declared a conservation zone, off-limits to the public. Forever.

At a special meeting starting at 7 p.m. this Monday, Feb. 6, Hudson council will adopt a revised 2017 budget and triennial investment plan. Indications are this administration will slash $1 million from the $13M budget adopted in December. Expect across-the-board cuts, including reduced grants to local organizations and events. The regular February council meeting follows.